Blog: Our Lady of Good Counsel

Our Lady of Good Counsel. Dennistoun, Glasgow.

Architect: Gillespie Kidd and Coia

Completed in 1968

Had you been asked to imagine a category A listed Catholic church, you would’ve been forgiven for imagining images of spires and a crucifix form, with tall stained-glass windows populating the elevations which then allow light to cascade upon a rigorously ordered nave. However, this time you couldn’t be more wrong. Almost bunker-like in its brutalist appearance, Our Lady of Good Counsel lacks almost any architectural characteristics of a church and had it not been for the cross above it’s doors you may not have even thought it a church. Yet it remains Glasgow’s only category A listed post war church, and the recipient of both a RIBA regional prize and the Civic Trust Award.

By this point the architects, Gillespie, Kidd and Coia, had been designing churches for the Archdiocese of Glasgow for almost a decade but their work at Our lady of Good Counsel remains one of their finest. Although lacking in traditional elements, the copper clad roof rakes in two directions to mimic a classical spire and immediately catches the eye of any passers-by. Devoid of any statues and ornamentation, the two gables consist of only the facing brick they are constructed from, however the scale of the northern gable gives it immense presence within its residential setting. As you turn the corner towards the eastern face, the brickwork starts to open to reveal the entrances to the Church interior, both of which marked out with a stepped brickwork detail which then allows the stairs to be almost enveloped by the building. A row of windows sits atop the brickwork wall, but nothing like the tall windows previously mentioned, instead they are almost domestic in scale, with the deep eaves of the copper roof above projecting far beyond them.

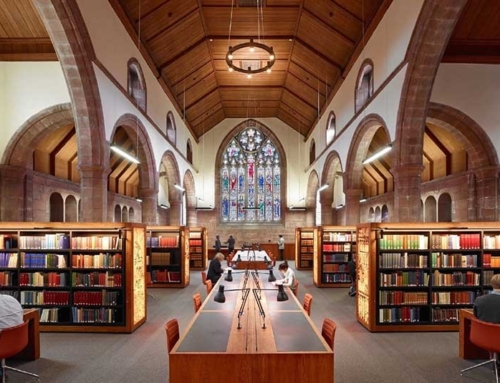

However, it is within the church that it becomes obvious why this building enjoys the status it has. As with most of their church’s, the architects have laden the building with religious symbolism. The external stair continues into the church’s irregular quadrilateral nave space, symbolic of the congregation’s rise into a spiritual place. Upon entry they were greeted with a bespoke baptismal font, as they all were the first time they were brought to become a part of the church. The space makes the use of the immense height gained by the roof shape, which reaches it’s point on the northern gable, above the sanctuary and the altar giving it an almost imposing nature as the most important space within the church. Finally, as with St. Paul’s, a bespoke commission of Christ upon the cross occupies the topmost space within the church, off centre so that to be visible from the entire congregation.

But the most interesting part of the interior is how light is brought into the space in two ways. The roof steps on the western face to allow for a row of glazing along the length of the nave, allowing light to then pass down into the central space creating this striking first impression as you enter what you would imagine to be a dark space. In doing so the material palette becomes much softer, the brick and concrete is warmed by the light and the timber accents give it that more familiar church feeling. The second method that light enters the space is also the most unique and completely transforms the perception of the space. Within the vertical element of the western step in the roof are hidden windows, each of which are stained with a single colour and with a deep reveal to the interior which is then masked with a perforated timber screen. Similar to Corbusier’s Ronchamp Chapel, there is no obvious pattern to these glazed elements and with the deep reveals and masking they provide no views of the setting beyond. However, the affect that is achieved is that throughout various points of the day, rays of pure coloured light are beamed down upon the congregation, as if the roof is casting it’s own rainbow, completely transforming the interior of the brutal church into something far more welcoming and special.

The Catholic Church may have begun the process of widespread modernisation following the closure Second Vatican Council in 1965, however Gillespie Kidd and Coia in 1964 were already ahead of the game. This truly unique piece of architecture is a perfect demonstration of how classical elements of a traditional typology can be manipulated and tested in order to present a completely new take deserving of all its plaudits and it’s reputation as Glasgow’s only category A post war church.